POST 25: "Put Your Dreams Away"

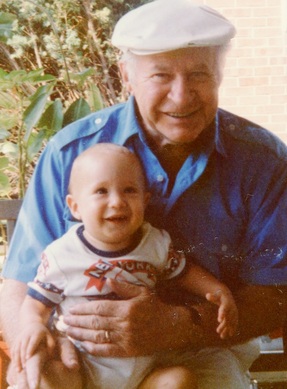

Andrew, age 1, with Grandpa Joe, in Cleveland, Ohio, 1991.

Andrew, age 1, with Grandpa Joe, in Cleveland, Ohio, 1991.

“Let us not be satisfied with just giving money. Money is not enough, money can be got, but they need your hearts to love them. So, spread your love everywhere you go.” Mother Teresa

The unfinished business with dad was even more complicated because we had an established close bond, I loved my stepmother, but it had been severely strained as a casualty of the fighting between my parents.

Money was a tender topic with my dad, probably because he had failed professionally and made so little in his later years. With the guidance of a therapist, I tried to talk to him about this, ask him for help that we needed. He declined to help and he declined to talk. I was devastated.

After mom died, I entered my final year at the Columbia University School of Social Work. I had to fill out all the financial aid forms. Columbia at the time still required even of its independent adult students parental income information. My mother had provided this without a problem. I was advised to approach my dad. I had ominous feelings about this. I explained to my dad what the school required, that no, I was not asking him to contribute financially to my education. Just please, fill out the damn form.

He balked. The school held firm. I could believe the scenario that was unfolding. Would my final year of social work school be jeopardized because my father didn’t want to cooperate? I went to the Financial Aid Office and requested their help. They called my dad and a compromise was achieved: he would provide the information to them directly, so long as I never saw it. While my head understood to a point, my heart just felt jerked around. On the surface we remained cordial and pleasant, but deep down there was a chasm. I always thought we would have a nice sit-down and clear the air. However we rarely saw each other; he was in Cleveland and we were in New York. The impasse ossified.

Then, at the same time my marriage started heading south, I got the news that dad was diagnosed with an aggressive, fast-moving form of Alzheimer’s Disease. His once brilliant mind was rapidly reduced to forgetfulness, then disjointed sentences, scrambled memories and then confused emotions. I bitterly regretted my stubbornness in not talking with him sooner. Before long he was soon moved to an assisted care facility.

It was 1998, the year Frank Sinatra died, the crooner of my father’s era. Like Sinatra, dad was a romantic, a drinker, a ladies’ man. So when Barry came out with a tribute album Manilow Sings Sinatra I was drawn to “Put Your Dreams Away,” a signature song of Sinatra’s career, because I soon realized that there would be no dream of reconciliation with my father.

So, as Mother T. always advised, I prayed. I prayed that in some way, God would heal our relationship, now that words no longer functioned.

That’s when the dreams started.

Around New Year's I had a restless dream about my dad. He was calling. Shouting. I couldn’t make out his words.

The next morning I telephoned my stepmother Margie and told her. “The night nurse said he was calling out your name.”

So I prayed some more. Over a course of several months, Spirit connected us in prayer and dream. I had a frightening dream one night, of my father being surrounded by vicious animals. I prayed about it. “He is facing unfinished business, keep praying for him” was the answer.

So I kept praying. I made a visit to Cleveland and visited him, now in a state of twilight. He was non-responsive. However I still talked to him because I believed his spirit was intact and he could understand. I thanked him for his love and for making my childhood bearable. For taking me to ballgames and teaching me how to fill out a scorecard. For all the candy bars, ice cream cones and comic books, and later the Mother Jones and other progressive magazines he read and later passed on to me. I also told him how hurt I was when he didn’t answer my letter and I regretted the gulf between us. I said I was sorry for my pigheadedness.

I was sad that his bright mind had been cursed with growing oblivion. There was no response. I told him that I forgave him and that I was sorry too. I knew, somewhere, somehow, God would see to it that he got the message.

The inevitable came. My brother Michael called me on a chilly April afternoon.

“Hospice says you’d better come now if you want to see dad alive. He’s got about 24 hours.”

I started to make plans. As I picked up the phone, some sly demon took told of me. It whispered in my ear: “If you go, you will have to just return later in the week for the funeral. The flights are so expensive. Why book two flights? Just wait until the end of the week.”

Images of my dad, The Cheapskate, surfaced with fury and indication. “When did he sacrifice for you?” The demon gleefully probed. “He was willing to jeopardize your education.” The revelations of unpaid child support that made life hard. I put down the phone. I walked around the room, deep breathing.

I whispered my 911 prayer: "Jesus, help." “What do I do?”

Then I heard another old, familiar voice, the one that signaled peace and grace: “If you do not go now you will regret this for the rest of your life.”

That was it. I made the reservation. That night I gathered with Margie, my brothers, and a few other family members. I held my dad’s hand. In my pitchy voice I sang hymns and recited prayers. He passed quietly in the middle of the night. I felt whole. Yes, I went back to New York. I returned to Cleveland a few days later with Andrew. This time I gave the eulogy at my father’s funeral.

When we returned home, it all seemed unreal: the dreams, the angelic messages, the inner healing that transcended the miles and years. After a few weeks I finally couldn’t stand it any longer. “God,” I implored, “please give me a sign that dad is okay, that he is safe with you, and this all wasn’t a crazy, desperate delusion on my part.”

I immediately felt foolish for uttering such a sophomoric prayer.

I walked to my children’s room to check up on three-year-old Hannah who was playing blissfully with her stuffed animals. Hannah had not been to the funeral. She had met her grandpa Joe only once, the year before. She certainly had not heard the silent request I uttered in the next room. As I walked in the room, Hannah looked up. She seemed to look beyond me.

“Hello Grandpa Joe!” she exclaimed. Then she went back to her toys.

“Put Your Dreams Away” was one of Sinatra’s theme songs that Barry sang as well. That day, that Grandpa Joe day, I knew it was true, as it says in the song, “and so it’s time for a new start.” It truly was.

A new start for us.

Notes:

http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/m/mothertere153714.html#uIbZM5rMhbXFmWB3.99

Give the gift of music to the next generation through donations to:

The Manilow Music Project

8295 South La Cienega Boulevard

Inglewood, CA 90301

[email protected]

Click here to go to the next post or click here to return to the previous post.

The unfinished business with dad was even more complicated because we had an established close bond, I loved my stepmother, but it had been severely strained as a casualty of the fighting between my parents.

Money was a tender topic with my dad, probably because he had failed professionally and made so little in his later years. With the guidance of a therapist, I tried to talk to him about this, ask him for help that we needed. He declined to help and he declined to talk. I was devastated.

After mom died, I entered my final year at the Columbia University School of Social Work. I had to fill out all the financial aid forms. Columbia at the time still required even of its independent adult students parental income information. My mother had provided this without a problem. I was advised to approach my dad. I had ominous feelings about this. I explained to my dad what the school required, that no, I was not asking him to contribute financially to my education. Just please, fill out the damn form.

He balked. The school held firm. I could believe the scenario that was unfolding. Would my final year of social work school be jeopardized because my father didn’t want to cooperate? I went to the Financial Aid Office and requested their help. They called my dad and a compromise was achieved: he would provide the information to them directly, so long as I never saw it. While my head understood to a point, my heart just felt jerked around. On the surface we remained cordial and pleasant, but deep down there was a chasm. I always thought we would have a nice sit-down and clear the air. However we rarely saw each other; he was in Cleveland and we were in New York. The impasse ossified.

Then, at the same time my marriage started heading south, I got the news that dad was diagnosed with an aggressive, fast-moving form of Alzheimer’s Disease. His once brilliant mind was rapidly reduced to forgetfulness, then disjointed sentences, scrambled memories and then confused emotions. I bitterly regretted my stubbornness in not talking with him sooner. Before long he was soon moved to an assisted care facility.

It was 1998, the year Frank Sinatra died, the crooner of my father’s era. Like Sinatra, dad was a romantic, a drinker, a ladies’ man. So when Barry came out with a tribute album Manilow Sings Sinatra I was drawn to “Put Your Dreams Away,” a signature song of Sinatra’s career, because I soon realized that there would be no dream of reconciliation with my father.

So, as Mother T. always advised, I prayed. I prayed that in some way, God would heal our relationship, now that words no longer functioned.

That’s when the dreams started.

Around New Year's I had a restless dream about my dad. He was calling. Shouting. I couldn’t make out his words.

The next morning I telephoned my stepmother Margie and told her. “The night nurse said he was calling out your name.”

So I prayed some more. Over a course of several months, Spirit connected us in prayer and dream. I had a frightening dream one night, of my father being surrounded by vicious animals. I prayed about it. “He is facing unfinished business, keep praying for him” was the answer.

So I kept praying. I made a visit to Cleveland and visited him, now in a state of twilight. He was non-responsive. However I still talked to him because I believed his spirit was intact and he could understand. I thanked him for his love and for making my childhood bearable. For taking me to ballgames and teaching me how to fill out a scorecard. For all the candy bars, ice cream cones and comic books, and later the Mother Jones and other progressive magazines he read and later passed on to me. I also told him how hurt I was when he didn’t answer my letter and I regretted the gulf between us. I said I was sorry for my pigheadedness.

I was sad that his bright mind had been cursed with growing oblivion. There was no response. I told him that I forgave him and that I was sorry too. I knew, somewhere, somehow, God would see to it that he got the message.

The inevitable came. My brother Michael called me on a chilly April afternoon.

“Hospice says you’d better come now if you want to see dad alive. He’s got about 24 hours.”

I started to make plans. As I picked up the phone, some sly demon took told of me. It whispered in my ear: “If you go, you will have to just return later in the week for the funeral. The flights are so expensive. Why book two flights? Just wait until the end of the week.”

Images of my dad, The Cheapskate, surfaced with fury and indication. “When did he sacrifice for you?” The demon gleefully probed. “He was willing to jeopardize your education.” The revelations of unpaid child support that made life hard. I put down the phone. I walked around the room, deep breathing.

I whispered my 911 prayer: "Jesus, help." “What do I do?”

Then I heard another old, familiar voice, the one that signaled peace and grace: “If you do not go now you will regret this for the rest of your life.”

That was it. I made the reservation. That night I gathered with Margie, my brothers, and a few other family members. I held my dad’s hand. In my pitchy voice I sang hymns and recited prayers. He passed quietly in the middle of the night. I felt whole. Yes, I went back to New York. I returned to Cleveland a few days later with Andrew. This time I gave the eulogy at my father’s funeral.

When we returned home, it all seemed unreal: the dreams, the angelic messages, the inner healing that transcended the miles and years. After a few weeks I finally couldn’t stand it any longer. “God,” I implored, “please give me a sign that dad is okay, that he is safe with you, and this all wasn’t a crazy, desperate delusion on my part.”

I immediately felt foolish for uttering such a sophomoric prayer.

I walked to my children’s room to check up on three-year-old Hannah who was playing blissfully with her stuffed animals. Hannah had not been to the funeral. She had met her grandpa Joe only once, the year before. She certainly had not heard the silent request I uttered in the next room. As I walked in the room, Hannah looked up. She seemed to look beyond me.

“Hello Grandpa Joe!” she exclaimed. Then she went back to her toys.

“Put Your Dreams Away” was one of Sinatra’s theme songs that Barry sang as well. That day, that Grandpa Joe day, I knew it was true, as it says in the song, “and so it’s time for a new start.” It truly was.

A new start for us.

Notes:

http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/m/mothertere153714.html#uIbZM5rMhbXFmWB3.99

Give the gift of music to the next generation through donations to:

The Manilow Music Project

8295 South La Cienega Boulevard

Inglewood, CA 90301

[email protected]

Click here to go to the next post or click here to return to the previous post.